| MATTIA MORENI | Exhibition 2019 | |

| Magazine |

Mattia Moreni was born in Pavia in 1920 and died in Brisighella (where he had moved to in 1966) in 1999. From the mid-1930s, Moreni favoured a naturalistic vision of things, figures, houses and landscapes, and, towards the 1940s, also portraits. It was a language that had developed during his studies at the Albertina Academy of Fine Arts in Turin, where he proposed introspective images with expressionistic tones. His first solo exhibition dates from 1946, at Galleria La Bussola in Turin, with paintings and drawings from the period when his visionary expressionism and destabilizing images took on the semblance of close-up compositions of fruit or animals. Standing out in these studies are some important aspects for his following career: the inclination to propose totalizing images, with a shallow perspective crowded with the “enlarged presence of objects” and an expressionistic, deforming tremor which went “way beyond the dialectal and illustrative and folkloristic order” of local derivations of “Nordic or more precisely Flemish models”. As of the second half of the 1940s, Moreni opened up to a more international dialogue, fascinated by non-figurative neo-cubist stimuli. In 1948-49 his research took an abstract bent (Galleria del Milione, Milan, 1947 and 1949; Venice Biennale, 1950) and his language gained international recognition with his participation at the São Paulo Biennial in Brazil (1951) and Mostra Nazionale d’Arte Contemporanea in Milan (1952).

After a period in Turin when the artist veered towards a certain expressionism, and participating in post-cubism, he became part of the “Gruppo degli Otto” (along with Afro Basaldella, Renato Birolli, Antonio Corpora, Ennio Morlotti, Giuseppe Santomaso, Giulio Turcato and Emilio Vedova) who, with the backing of Lionello Venturi, proposed to go beyond the fracture between realist and abstract artists that happened in 1950 with the end of the “Fronte Nuovo delle Arti” experience. With the intent of overcoming this antimony, the group proposed abstract-concrete painting at the Venice Biennale in 1952. Moreover, Moreni was one of the first to adopt novel informel lines.

From then until the early 1960s, the artist reached a new level of emotional tension as he met with a primitive and wild nature in his many stays in Romagna and Lazio. It was a nature he rendered with great force of expression, with macro-structures and bright colour contrasts, making the colour into both matter and gesture, in typically informel style.

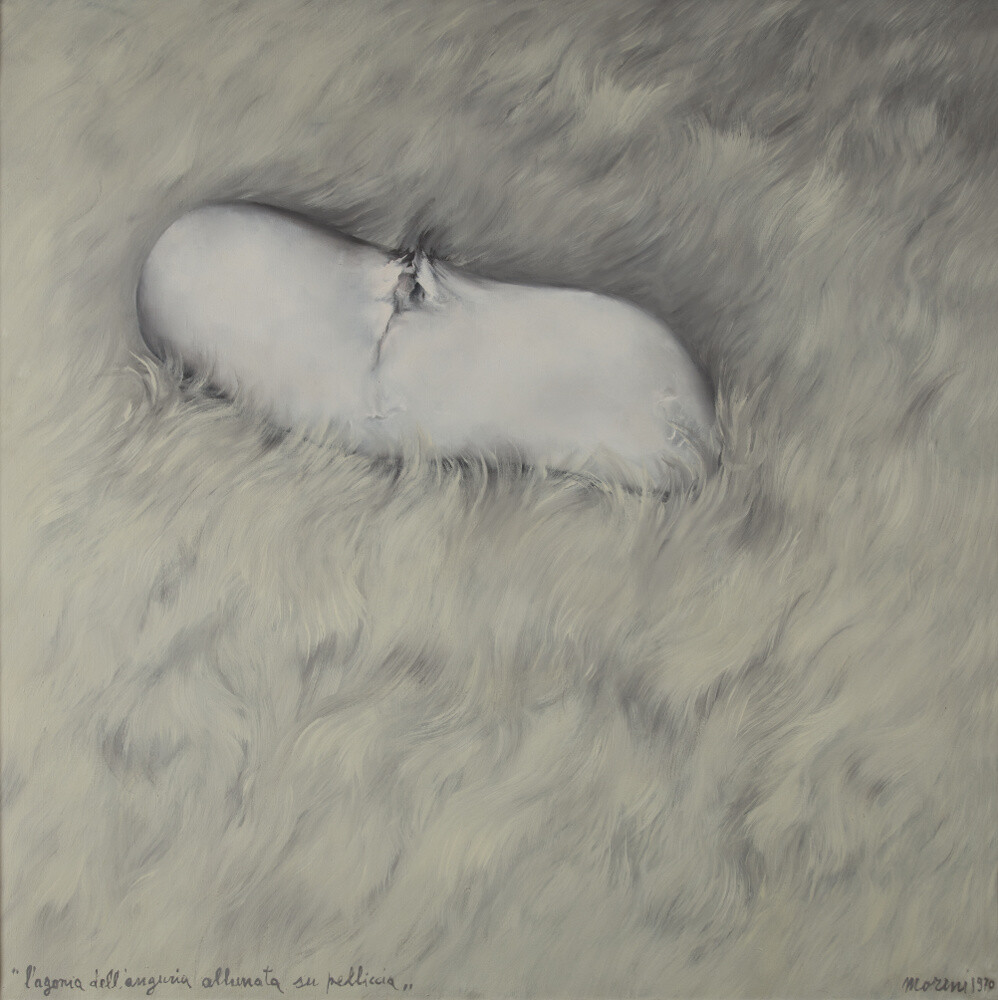

After about a decade, Moreni was one of the youngest artists headlining European informel, with acknowledgements at international level and participations at the São Paulo Biennial in Brazil (1953 and 1954) and Documenta in Kassel (1955). In the middle of the 1950s (1956), he moved to Paris for a decade. Here he met Michel Tapié and exhibited at the Galerie Rive Droite with the biggest names in the informel current. The gestures in the paintings from this half of the 1950s combine signs and matter (Venice Biennale, 1956; Documenta, Kassel, 1959). In 1960, the matter tended to become denser and shapes became recognizable once more; from simulacra of human figures we go to trees, from clouds to placards, huts, fields and watermelons (Museo Morsbroich, Leverkusen, 1963; Kunstverein, Hamburg, 1964; Museo Civico, Bologna, 1965), the latter the protagonists of this post-informel period (Venice Biennale, 1972; Pinacoteca Comunale, Ravenna, 1975). Moreni investigates the decadence of contemporary society, between Eros and Thanatos: decay, death and splendour become the themes of works whose tone, however, is never downbeat. Pelliccia, fur, a new iconic, erotic presence, becomes part of this line of research; he evolves his pictorial language, refining his methods and the consistency of the layers in a manner that would accompany him to the end of his artistic career. The decadence of the human species is also displayed through large female genitalia and combinations of humanoids-computers, bringing us to the virtuoso cycle of Atrofiche and Marilù paintings on large canvases (Santa Sofia di Romagna, 1985 and 1991). In 1983 the artist begins to theatralize his paintings, in an analytical demonstration of the “regression of the species and fine arts” resulting in a series of schematic images, words with humoristic pictorial gestures: Pattumiere (1983-1984), Tubi (1984), Lampadine (1984-1985), Geometrie indisciplinate (1984-1986). Examples of these works were shown at a at a solo exhibition in 1987-88 in Milan, where they also tested new, more audacious and louder spectrums of colour (Arezzo, 1989; Paris, 1990). Between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s, the artist devoted himself to self-portraits, with a series of Autoritratti denouncing an evolution in themes and language, accompanied by handwritten scripts of the image with no chronological correspondence to the images (dealing with his past, but also a hypothetical future). In this phase, the force of expression, rather than identification of the actual psychosomatic features, continued to take precedence (XXIX Premio Campigna, Santa Sofia di Romagna, 1985; and again in the same place, 1991 and 1992). The relations between image, background and script would continue to be simplified, resulting in the essential Umanoidi (1993) figures, a vast series of works displayed in two solo shows in 1994-95 in which the features consist of a technological box, alluding to a computer, which replaces the person’s face and mind (Ravenna, 1996; Faenza, 1999). […] “Moreni paints the premonition that, on its way towards an electronic and digital future, art will never be the same again. Like humans, now at one with computers” (Claudio Spadoni). Popping up in the works from his last years, 1997, 1998 and 1999, are arms, legs and feet, or “fashion shoes”, or fruit: a “mechanical pear”, “electronics”; objects such as a table or a car. Mattia Moreni’s works are found in many collections in Italian and international museums, amongst which, to name a few: GNAM in Rome, Mart in Trento and Rovereto, MamBo in Bologna, Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, Museo del Novecento in Milan, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Turin, Museo d’Arte della Città di Ravenna; VAF-Stiftung in Frankfurt, Museu de Arte Moderna and Museu de Arte in São Paulo, Brazil, Galleria d’Arte Vero Stoppioni in Santa Sofia, Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain in Liège, Nationalgalerie in Berlin and Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen. In 2016, the Mattia Moreni general catalogue was created, edited by Enrico Crispolti and published by Silvana Editoriale, with the help of Galleria d’Arte Maggiore in Bologna (site of the archive of the artist’s work since 1999) which curated many of his exhibitions: Mattia Moreni – Apparizione del Narciso and Mattia Moreni – L’ultimo grido, Bologna (2005), Preludio – Primo decennio 1941-1953, Museo Civico delle Cappuccine in Bagnacavallo (2008), Mattia Moreni – Il percorso interrotto. Ultimo decennio 1985-1998, Kunsthaus in Hamburg and Antichi Magazzini del Sale in Cervia (2008), Mattia Moreni – Ah! Quel Freud…, at Galleria d’Arte Maggiore in Bologna (2016).

In 2019, Galleria Il Ponte in Florence is dedicating a monographic exhibition to the artist: Mattia Moreni dal Paesaggio al Computer |’50-’90.